The Four Styles of Confidence on a Team

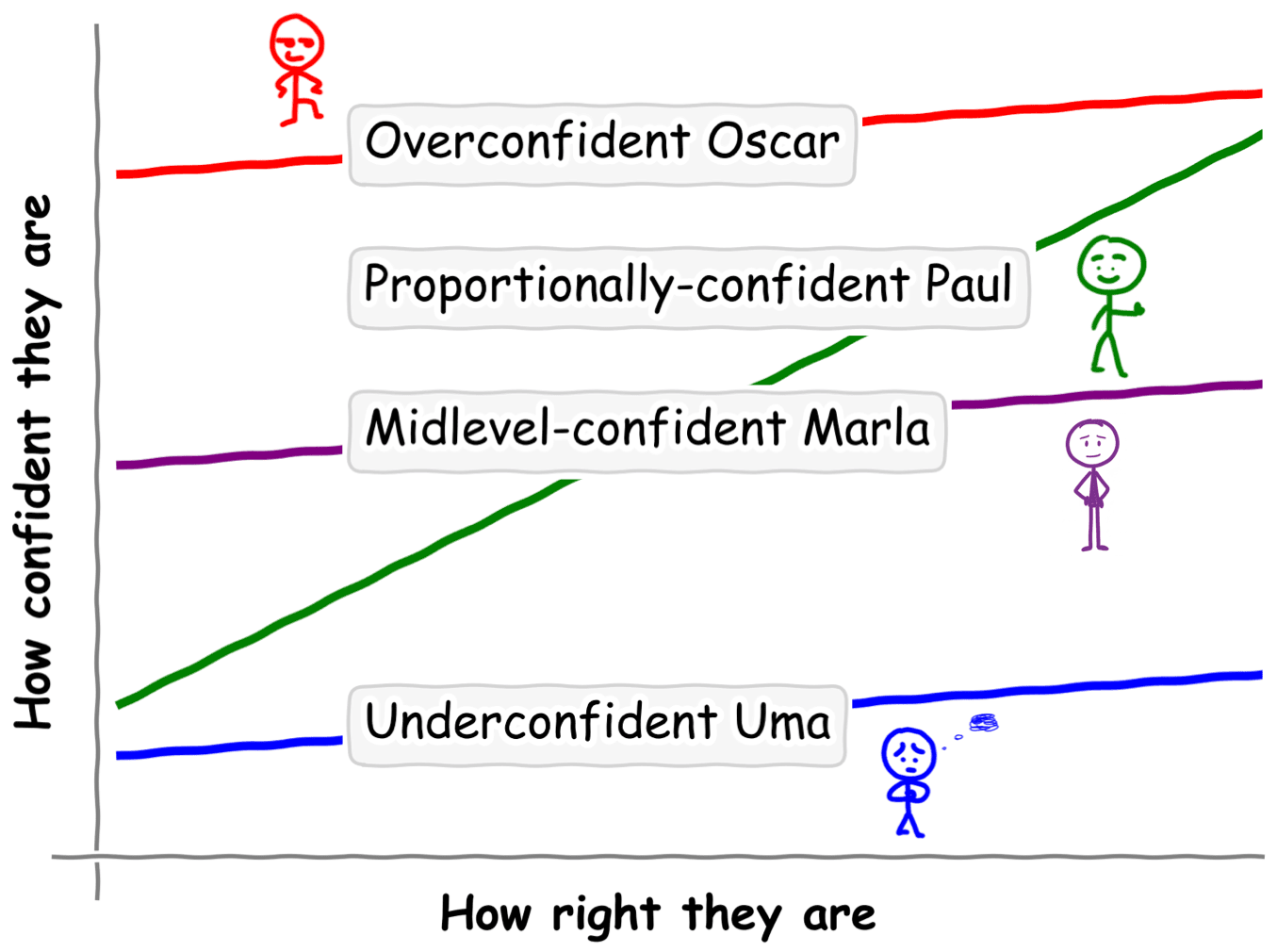

I think of everyone as having a property: How strongly they state their opinions, divided by how right they actually are.

There are four common buckets.

People with high ratios are overconfident. They always pound the table, even when they’re wrong.

Those with low ratios are underconfident. They rarely speak up.

Midlevel-confident people speak up, but never with either conviction or doubt. They are always “mid” confident.

And finally, the proportionally-confident are good at estimating how likely they are to be right, and communicating that confidence level to others. This is an underrated skill.

Confidence styles impact teams

Let’s order these four confidence styles by how they impact teams, from worst to best.

The worst type is overconfidence. When someone is overconfident you may not get the benefit of any of the brains in the room, because conversations end too early.

Suppose Overconfident Oscar makes a strong assertion. One person may think “If Oscar is so confident then maybe I’m wrong, so I won’t push back.” Someone else may think “Pushing back requires too much energy and social capital, so I’m going to pick my battles.” People withdraw.

Underconfidence is somewhat better. Their teams miss the benefit of their brain, because they don’t speak up, but at least conversations don’t stop prematurely.

Then there is midlevel confidence. Teams get their input, but no signal about how to weigh it.

And finally, in the #1 spot, is proportional confidence. Teams get their input, and signal about how likely it is to be right. We should all strive to be proportionally confident.

How to become proportionally confident

Both individuals and teams can learn how to become proportionally confident. Let’s start with the how-to guide for individuals, and then turn to the manager toolkit.

Learning to estimate how likely you are to be right

Although there are different playbooks for fixing over- versus underconfidence, both begin with knowing how likely you are to be right.

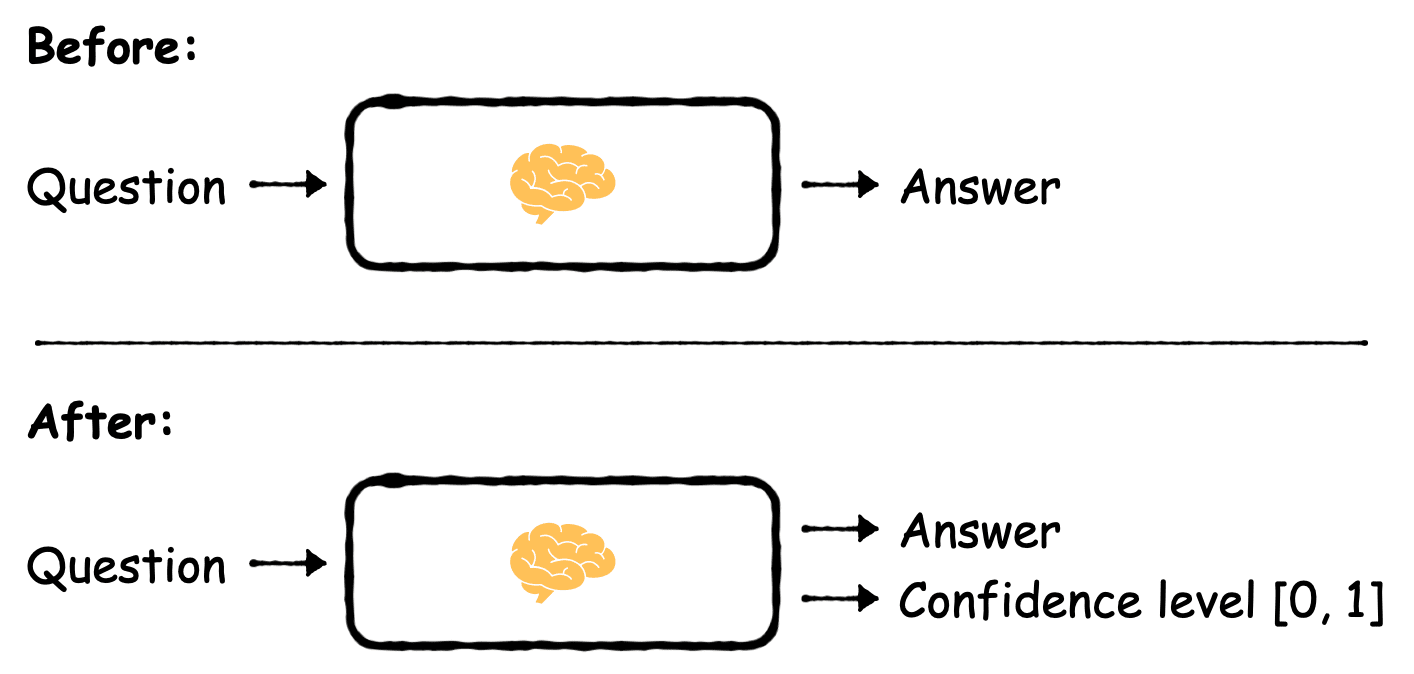

When you learn this skill, your thinking goes from one dimension — What do I think? — to two dimensions: What do I think, and how likely am I to be right?

Adding confidence levels to your thinking is like adding hot-water plumbing to a Victorian-era house that only has cold-water pipes. It takes a lot of work. You have to go one by one through every mental model you reason with, and watch it to estimate how often, and under what conditions, it is accurate.

For example, I’ve interviewed hundreds of recruiting candidates over the years, and in addition to tuning my scores for candidates, I’ve also tried really hard to know how likely my scores are to be right. [1]

You can develop this skill by tracking your positions against what actually happens in the end. Pay extra attention when you make a confident decision that turns out to be wrong.

Knowing how likely you are to be right produces a bonus: It makes you more right anytime you combine reasoning from multiple mental models, which is very common, because you’ll be better at reconciling conflicting information. For example, suppose you are considering investing in a startup. The market seems great but the team seems like a B+. The more accurately you estimate how likely your team assessment is to be right, the better the overall decision you can make. [2]

Fixing overconfidence

Overconfident folks habitually try to persuade others without inviting pushback. This behavior squelches conversations, resulting in wrong answers and, in some cases, resentment. Fortunately overconfidence can be fixed and the potential gains are huge for you and your team.

Differentiating between when you are trying to persuade, versus discover

Be clear with yourself about when you are trying to persuade, versus trying to discover a truth. Do not attempt to do both at the same time. As Paul Graham wrote, “Writing to persuade and writing to discover are diametrically opposed.” That’s true in writing, and it’s true in conversations.

Sales roles sometimes train people to exude confidence when persuading, and they misapply that skill to decisionmaking. It’s great to be skilled at persuading someone of something [3], but it’s the wrong toolkit when you’re working with a team trying to find the best solution to a problem.

Being open to changing your mind

When I was young I was sharp enough to defend incorrect ideas, so I would pick whatever position felt right, and then defend it vigorously. I could usually find technicalities or ambiguities in opposing arguments.

That’s a great way to be wrong about a lot of things.

As Jeff Bezos puts it, The people who are right the most often change their minds the most often. This is my all-time favorite business one-liner.

The inverse is also true: Sticking to your guns will make you wrong more often.

The best leaders update their opinions frequently. For example, here is Steve Jobs in 1995:

“I don’t really care about being right — I just care about success. You’ll find a lot of people who will tell you I had a very strong opinion and they presented evidence to the contrary and five minutes later I completely changed my mind. I don’t mind being wrong, and I’ll admit that I’m wrong a lot. It doesn’t really matter to me. What matters is that we do the right thing.”

—Steve Jobs, The Lost Interview, filmed 1995

There are a few tactics you can use to build the skill of quickly changing your mind.

As Benjamin Franklin noted in his autobiography, it helps to say things like “I think…”, “It seems like…”, or “This isn’t a strong opinion, but…” to qualify your positions. Then your ego gets less attached to those positions, and you’ll have an easier time letting them go.

Additionally, find a team where you feel respected. Everyone feels less pressure to defend their positions when there is established respect and trust.

Fixing underconfidence

Normally underconfident people express confidence in inverse proportion to how much pressure they feel to get along, instead of how right they are.

Every human reading this is a social animal, and feels a desire to please others, fit in, and avoid conflict.

This drive to fit in can be a problem. It undermines trust because trust is built by having and resolving conflict. It deprives your team of the perspectives you have to offer. And it can lead to burnout and disconnection because you are suppressing your inner truths.

The underlying dynamics are usually psychological. While this post is not the occasion to fully unpack them, we will cover a few types of solutions.

Calibrating your confidence ratio to others around you

Mechanistically, watch how often others are more confident and less correct than you. Increase your confidence until your How confident you are ÷ How right you are confidence ratio matches others on your team.

Who is responsible for which feelings?

You may be tempted to avoid conflict because you are taking responsibility for others’ feelings, but you are not responsible for others’ feelings.

You may be tempted to avoid conflict because you would feel shame if someone had a bad reaction to what you are saying. You are responsible for working through these feelings of shame.

Preparing scripts for high- versus low-confidence opinions

Practice speaking up when you are not very confident (“I think this is right, but I’m curious about what I may be missing…”), as distinct from when you are confident (“I feel confident that…”).

Which do you struggle with more? Write down a few phrases to use in both of these different situations that sound authentic to you.

Consuming other resources

See the books Radical Candor, Difficult Conversations, and Thanks for the Feedback for building skills in this area.

Fixing midlevel confidence

Midlevel-confident folks share their input, and do not crowd out others, but their teams get no signal about how to weigh their input. Decisions drag, risks hide in hedges, and postmortems reveal “We kinda knew, but no one put a stake in the ground.”

The solution is to start paying attention to confidence levels in your thinking and conversations:

- How confident are you?

- What would change your mind?

- Force rank lists — such as risks, solutions, etc — by likelihood or impact

- How bad would it be if we are wrong?

- Specify loose confidence intervals

- Vocally update your confidence level as discussions happen and new information is surfaced

For managers: Building proportionally-confident teams

It’s really fun to be on teams that are effective at combining everyone’s knowledge and thinking to get to the best answers. As a leader, you can’t just hope for this dynamic to emerge. You must deliberately build it into the work environment. I use three tactics for this: Hiring for proportional confidence, cultivating the right culture, and coaching team members directly.

Hiring well

The most important step is to screen for overconfidence during hiring.

It’s easy to tell if someone is overconfident: Just measure the average confidence of their opinions across a range of topics. How much force do they use in conversation? If it is always high, they are overconfident. You don’t even need to know the truth about what they’re discussing.

If you do know the material they’re discussing, then you can detect overconfidence even faster. How right are they, actually? When you push back on something they say, do they get curious and weigh the new information, or do they simply dig in?

It’s also helpful to avoid folks who would never add their perspective, although there is more margin for error here. Depending on the role, you may want to avoid hiring the top e.g. 10% of overconfident candidates and avoid the bottom 5% of underconfident candidates.

Finally, midlevel confidence is okay in most junior roles. For more senior roles, look for dynamic range in their confidence levels. Some answers should come back with confidence, and others should come back with an appropriate level of humility.

Cultivating the culture

Culture can be a great tool for creating great environments. That topic needs its own post, but as it relates to proportional confidence, I encourage everyone on my teams to change their minds easily and to expect that others will change their positions often as well.

Additionally, make sure leaders in your organization are aware of how seniority impacts discussion. Because people weigh input from more-senior people more heavily, senior folks need to downplay their confidence, or go last, when they want to encourage discussion.

Coaching

Give your team feedback on this skill. Nudge underconfident people to speak up and share their thoughts. Have direct conversations with overconfident people about its impact on the team, point them to resources like this post, and give them same-day feedback when you feel they may need course corrections.

When it all comes together

One of the fun moments on teams is when someone with high judgment and a proven track record of being proportionally confident pounds the table on something. In a healthy culture, the team knows this signal is meaningful and can rally around the decision, solving a puzzle that lower-functioning teams couldn’t.

FAQ

What about “strong opinions, loosely held”?

“Strong opinions loosely held” is three-quarters right. It’s always good to have loosely-held opinions, so that half is right, but opinions should only be strong when they are right. Assuming opinions are right half the time, “strong opinions” is right half the time, so “strong opinions loosely held” is right ½ + ½ × ½ = ¾ of the time.

I’m being a bit glib. The point is that the ‘strong’ part should be earned, not a default setting.

But aren’t there high-performing teams who yell at each other?

There is an exceptional case where “strong opinions loosely held” is fully ideal. In specialized teams where the members readily push back against strongly-stated opinions with their own, and where strongly-stated opinions encourage more discussion. This is a rare team dynamic, but apparently Steve Job’s executive team at Apple operated like this — his reports would have intense discussions with each other in a volatile and emotionally-charged environment. After Steve left, Tim Cook unwound this culture entirely. It still seems like an antipattern for the vast majority of teams, but I can imagine it working in exceptional circumstances.

“Experts”

Experts tend to play on the right side of the “How right they are” axis, so it makes sense for them to express a lot of confidence in their opinions. This gets them into hot water when they shift to the left side of the axis without realizing it, either when they stray from their circle of competence or when there’s been a shift in the underlying topic that has deprecated their knowledge.

“Founder mode”

Paul Graham recently wrote about Founder Mode, and the Social Radars podcast recently interviewed Brian Chesky about it.

Brian describes becoming relatively underconfident as Airbnb grew. “The more successful we got, the more I lost my confidence,” he said. I think what happens is that when companies are small everyone operates with proportional confidence, and as you scale you hire career executives who often became successful, in part, by being overconfident. So founders lose control as their execs’ overconfidence takes over decisionmaking, and Founder Mode is the act of recalibrating by founders asserting their input more confidently.

Conclusion

Teams need more than merely smart people. They need folks who can estimate how likely they are to be right, and can communicate their level of confidence effectively.

At the individual level, don’t be underconfident, but especially don’t be overconfident. Overconfidence can be fixed, and if you’re working on teams solving hard problems then fixing overconfidence will be one of the best unlocks of your career.

When building teams, avoid hiring overconfident people, create a culture that encourages people to change their minds, and give people feedback on this skill.

Then you’ll get the benefit of all the brains in the room.

Next up

“Team attitude” post coming soon! Sign up to receive an email when I publish new posts below (low frequency):

Footnotes

[1] It’s a particular blessing when someone you scored low gets hired anyway because you get to see the underlying truth once they are onboarded.

[2] In the case of startup investing I suggest writing down your startup predictions and going back to them 3 to 8 years later. It’s a sobering, but highly-educational experience.

[3] Focusing on persuasion is often an ineffective way to persuade anyway. If you believe in what you’re selling, have “discover” conversations by asking lots of questions and without holding tightly to your ideas.